|

|

|

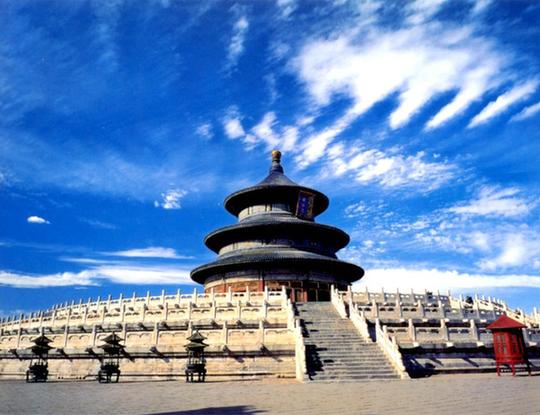

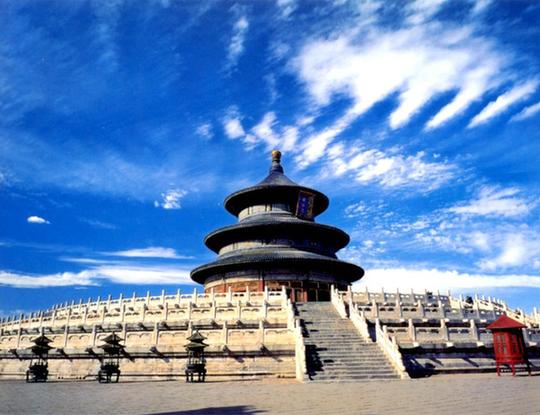

The Temple of Heaven

|

As an ancient capital and modern metropolitan, the city of Beijing features a complicated mixture of building styles. Imperial palaces and commoners' traditional houses stand side by side with modern glass-walled high-rises. Across the city, modernity has been sweeping into the old neighborhoods through the construction of tall office buildings and residential high rises replacing old-fashioned four-section courtyards and hutongs. In some places, monstrous skyscrapers seem to be somewhat out of place. But this is a tide of urban development deemed impossible to be turned around. What's necessary now is a serious second thought on knocking down old neighborhoods which are an inherent part of the city's character.

|

|

|

Beihai Park

|

The imperial palaces, gardens and altars with their grand scales and unparalleled craftsmanship are still the most awe-inspiring buildings. Those structures, built with wood and bricks, follow specific construction principles without comprising a single item down to the very last detail. Stepping into the Forbidden City, Beihai Park, the Temple of Heaven or the Summer Palace, one is easily touched by their grandeur and delicate decorations. Those architectures are testimony to the ingenuity of China's ancient designers, craftsmen and builders.

|

|

|

Siheyuan

|

The four-section courtyard (siheyuan) is another architectural trademark of Beijing. The currently still existing ones were built from the Qing Dynasty to the 1930s. They were owned either by noblemen, rich businesspeople or commoners. Those residences are enclosed spaces with houses on three or four sides. They embody the Chinese design concept of harmonizing human existence with Nature.

Nowadays the number of courtyards is declining dramatically. Some of the remaining units have been turned into restaurants, hotels, shops or bars. Some have become targets for property speculation. Some people who are still living in the run-down compounds are either waiting for the chance to move to better apartments or battling forced evacuation.

|

|

|

Nanluoguxiang

|

Beijing is also identified with hutongs, a word originating from Mongolian that means narrow street or alley. Hutongs connect the four-section courtyards in a neighborhood and deal with traffic flows. They first appeared during the Yuan Dynasty (1279 to 1368 AD). It is said that Beijing used to have up to 7,000 hutongs of various lengths and widths. Over the past several decades, however, the number of hutongs has declined considerably due to relentless urban development.

|

|

|

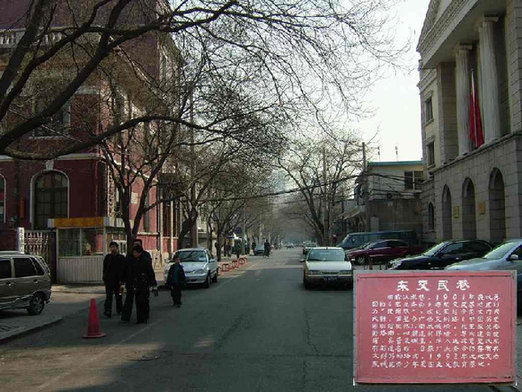

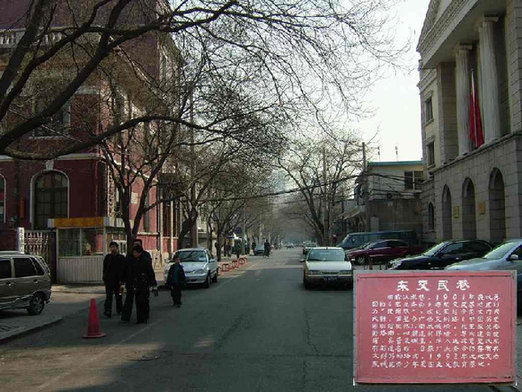

Dongxijiaominxiang

|

One of the most renowned hutongs is Nanluoguxiang (Southern Bell and Drum Alley). This nearly 800-meter-long alley, built in 1267 during the Yuan Dynasty, is now a hot tourist attraction lined with various bars, restaurants and small shops. The longest hutong is Dongxijiaominxiang which runs for 6.5 kilometers, whereas the shortest one stretches for merely a dozen meters.

Currently, the Chinese capital is also experimental ground for world-renowned architects. For example, Frenchman Paul Andreu designs the egg-like National Center for the Performing Arts situated to the west of Tiananmen Square; the futuristic buildings of China Central Television's new headquarters, designed by Ole Scheeren of Germany and Rem Koolhaas of the Netherlands, have attracted a lot of global attention. These, along with the National Stadium (the Bird's Nest) and the National Aquatics Center (the Water Cube), among some others, have become Beijing's new landmarks.

0

0

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)